A controversial plan by the Ethiopian government to expand the capital, Addis Ababa, is set to be scrapped after a key member of the ruling coalition withdrew its support.

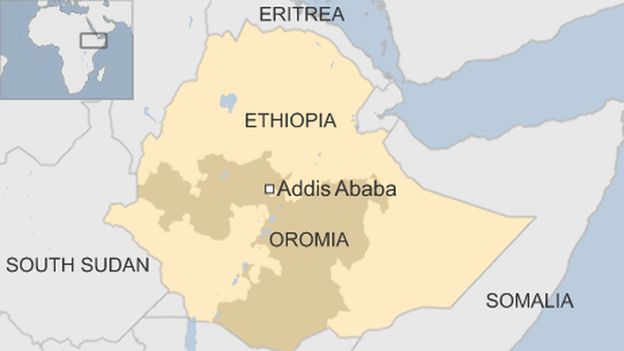

The expansion plan sparked deadly violence in the central-southern state of Oromia, which surrounds Addis Ababa.

Rights groups say that at least 150 protesters have died and another 5,000 have been arrested by security forces. Similar protests in May 2014 left dozens of protesters dead.

Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn had vowed on 16 December that his government would be “merciless” towards the protesters, who he described as “anti-peace forces”.

However in a surprising move, the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation (OPDO) said on 12 January that it had resolved to “fully terminate” the plan after a three-day meeting.

Rejection of official plans by government members is unprecedented in Ethiopia.

It is also historic, as it could be seen as acknowledging the legitimacy of the protests.

Any form of development the world over is going to upset someone, and the Ethiopian authorities have always said they would consult communities before bulldozing ahead.

But many Oromos, especially in the rural areas, view the expansion as a ploy by other ethnic groups, especially the Tigray and Amhara, to uproot them from their fertile lands under the guise of development.

The Oromo, who constitute about 40% of Ethiopia’s 100 million inhabitants, frequently complain that the government is dominated by the Tigray and Amhara who hail from north of the capital.

The governing coalition – the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) – has not yet issued an official statement on the future of its so-called “master plan” for Addis Ababa’s expansion.

But the extensive coverage of the OPDO statement by the tightly controlled state TV and pro-government websites indicates that the authorities will abandon it.

Ten armed rebellions

It is also surprising that the OPDO publicly expressed its condolences to bereaved families and pledged to assist those who lost property in the protests.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPSuch promises signal the depth of concern within the OPDO over the long-term impact of the protests.

The country’s political stability is fragile and it faces numerous domestic and international disputes.

Ethiopia has up to 10 domestic armed rebellions, mainly in the regions of Oromia, Tigray and Amhara and Gambella to the west.

There is also long-standing rebel activity in the south-eastern state of Somali, also known as Ogaden.

Besides the border dispute with Eritrea, which sparked a 1999-2000 war, the country shares volatile borders with Somalia and South Sudan.

Pacification of the country’s largest ethnic group removes one headache for the authorities.

Continuing the crackdown might have spurred Oromos to join rebel groups active in their region.

As long ago as 2002, late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi said Oromo students and opposition activists presented the most serious threat to his government.

So in the face of the large Oromo constituency, the OPDO realised that supporting the master plan undermined its grassroots support and influence within the EPRDF.

Political maturity

It is unclear what impact the move will have on the economy, which is one of the fastest growing in Africa.

Part of this growth is fuelled by state investment in large infrastructural projects.

Despite the impressive development, Ethiopia is ranked 173 out of the 187 nations surveyed in the last UN Human Development Index and has high poverty indexes, mainly related to the rising population.

This has put immense pressure on Ethiopia’s natural resources, including land, which has become a flashpoint.

Most of Ethiopia’s population is based in the rural areas and engaged in subsistence farming.

The state owns the land, leaving little incentive for farmers to engage in economically viable farming.

Some of the best land has also been leased to foreigners, further fuelling the tensions.

While shelving the plan would be a major retreat for the government, it is a sign of political maturity of the EPRDF, which has consistently been accused by rights groups of being heavy-handed towards dissent since coming to power in 1991.

The step, even if temporary, also removes the rug from under the feet of its numerous critics and will earn it political goodwill from Ethiopia’s international supporters, including Western donors.