The revelation that German spyware helped the Ethiopian authorities to locate, arrest and torture opposition followers, raises broader questions about the loopholes in Berlin’s export control procedures.

In its newly published report entitled “They Know Everything We Do,” Human Rights Watch (HRW) reveals how technology from countries including Germany is being used by the Ethiopian government to spy on civilians thought to be members of the opposition. In numerous instances, the surveillance activity has led to arrest, detention and even torture.

“They put me in cold water and applied electric wire onto my feet, they plugged the wire into the wall,” one interviewee told HRW. Like many of those rounded up by the authorities in Addis Ababa, he was presented with a list of his phone calls and accused of being a member of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) – a group seeking independence for the Oromo, the largest ethnic group in the East African country.

Besides highlighting Ethiopia’s ethnic tensions and the Orwellian potential of modern technology, the report begs some big questions about export controls in Western states prone to booming rhetoric on human rights. Western states such as Germany.

Cynthia Wong, senior researcher on the Internet and human rights at HRW, accuses Berlin of double standards. As a member of the Freedom Online Coalition, Wong says Germany has made “a very public commitment to promoting human rights online,” and should not be allowing technology such as FinSpy to be shipped to countries that might misuse it.

One wrong click

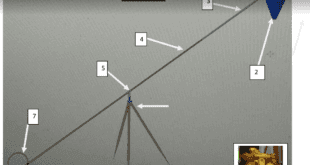

FinSpy is a remote monitoring tool installed onto a target’s computer via an email or fake software update alerts. Once activated, it can capture the user’s every online move and keystroke.

Spyware can be used to monitor every detail of online activity

Spyware can be used to monitor every detail of online activitySecurity researchers turned up a FinSpy server in Ethiopia in August 2012. At the time, the product was developed and sold by the UK-German firm Gamma International. Trading is now conducted by an independent Munich-based company operating under the name of FinFisher.

HRW says foreign firms providing products and services that facilitate illegal surveillance are risking complicity in rights abuses. Neither company responded to DW requests for information on their company’s rights policies.

Wong is calling for controls that would force companies to start thinking about the risks of their businesses being linked to human rights before they sell the technology.

“There should be some enquiry into what kind of government a company is selling to, who is actually going to be using the tools, and what for, what is the legal framework that government might be operating under,” Wong told DW.

Shared responsibility

The responsibility to screen buyers, however, does not lie solely with the manufacturers and vendors of equipment, but with governments. Barbara Lochbihler, chair of the Human rights Subcommittee of the European Parliament, says both parties feed the problem to which the only viable solution is a tight regulatory system on both a national and European level.

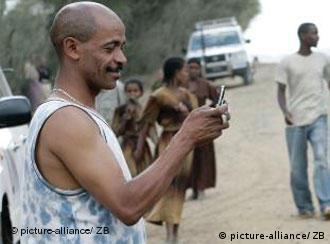

Authoritarian regimes are known to have used spyware to keep tabs of activists and members of the opposition

Authoritarian regimes are known to have used spyware to keep tabs of activists and members of the opposition“It will be difficult to fill every possible loophole and entirely prevent autocratic governments from gaining access to European surveillance technology,” she said, adding that it would prove particularly tough in the realm of dual use goods. “Still if complexity of the regulatory challenge was an excuse for political non-action, the European Parliament would probably be jobless.”

Lochbihler, who is a member of the Greens/EFA group, which has just launched acampaign, told DW that the current lack of regulation makes it possible to sell spyware to countries like Bahrain or Saudi Arabia without authorization. Siemens and Nokia provided malware tools to Iran prior to the 2009 revolution, and similarly Gamma spyware is known to have been used by the authorities in Manama.

“This has led to peaceful activists being imprisoned and tortured,” Lochbihler said. “But to date governments like mine in Germany have shied away from moving forward.”

Too many anomalies

In a statement to DW, Germany’s Federal Office of Economics and Export Control (BAFA) says companies seeking to ship technology that could be used for telecommunications surveillance in Syria or Iran, can not do so without a license, and that these are “fundamentally denied if there is sufficient suspicion that a product will be misused for internal repression.”

But Michael Spaney, European spokesman for the STOP THE BOMB campaign, which is working to prevent an Iranian nuclear bomb, says BAFA controls are seriously lacking. And not only in the telecommunications sector.

In November of 2013, a court in Hamburg found that the German export authorities had “endangered German foreign relations” by signing off on the shipment of valves to be used in the Arak nuclear reactor in Iran – a facility believed to be capable of producing enough plutonium for two atomic bombs in a single year.

“Germany allowed the export to this highly critical facility, although the US intelligence services had warned BAFA and the foreign ministry that Iran was looking to get hold of the valves,” Spaney said.

Spaney explains that when the vendor was approached by BAFA and warned that an offer from Tehran may be forthcoming, he had said he would not sell to a specific Iranian trader.

“He then handed in an application to say the valves were for a different use and facility and company,” the Iran expert told DW. “It went to BAFA, the Ministry for Economic Affairs and the Foreign Ministry, and export permission was granted.”

After the event is too late

In its verdict, the court ruled that “despite an early request from the US authorities to investigate and to prevent an export of the valves, the German authorities failed to do so.”

Citizens who took part in the 2009 Iran revolution were targeted through the use of spyware from Germany

Citizens who took part in the 2009 Iran revolution were targeted through the use of spyware from GermanySpaney describes it as scandalous that the BAFA allowed itself to be cheated so easily on an issue of such a high price. He believes the best way to prevent a repeat of what are potentially dangerous and damaging deals, is to regulate more tightly whilst simultaneously opening them up to wider debate. As things stand, exports are listed in an annual report which is presented to parliament as a fait accompli.

“That is far too late and means parliamentarians cannot get involved with anything they might find problematic,” Spaney said. “This is the main thing we have to address, but also as a nation whose economy lives from exports, we should be asking ourselves who we really want to do business with.”

Making a phone

Making a phone